- About

-

-

- About

-

ACGIH is a 501(c)(3) charitable scientific organization that advances occupational and environmental health.

-

-

- Subscriptions

-

- Science

-

-

- Science

-

This section has been established to help educate industry, government, and the public on what TLVs and BEIs are, and how TLVs and BEIs may best be used.

-

-

- Career Development

-

-

- Career Development

-

ACGIH is committed to providing its members and other occupational and environmental health professionals with the training and education they need to excel in their profession.

-

-

- Publications

-

-

- Publications

-

ACGIH has publications in many different areas that fit your needs in your field.

-

- Publications Store

- ACGIH Signature Publications

ACGIH Digital Library

If you need to purchase the Digital Library, click here.

If you have purchased and need to access the Digital Library, click here.

-

-

We here at ACGIH pride ourselves with the amount of talent and dedicated individuals that make ACGIH the strong, essential organization that it is today. We are greatly thankful to all of our volunteers who contribute their time, efforts and knowledge to help occupational, environmental, health and safety professionals be safe in their working environments.

We are dedicating this page to them. Following are selected participants who share how they came to be a volunteer and their thoughts on the industry itself.

If you’re interested in participating, please review the questions below and email your responses to Connie DiNuoscio at cdinuoscio@acgih.org. We’ll feature you in an upcoming edition of Exposure Weekly and add your profile to this page.

Featured in

Mar. 28, 2024

edition of

Exposure

Weekly.

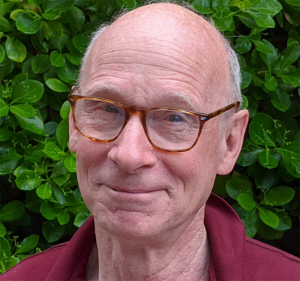

Neil J. Zimmerman, PhD, PE, CIH, FAIHA

Neil has over 45 years in the occupational and environmental health engineering field, including, industrial hygiene teaching and research; industrial hygiene consulting; indoor air quality consulting; and expert witness consulting. He is a Professor Emeritus of Industrial Hygiene, and currently serves as a Director on ACGIH’s Board of Directors.

What is your profession, and how many years have you been practicing?

- Environmental Engineering, 1971-74 (BS in Mechanical Engineering, 1971)

- Industrial Hygiene Professor at Purdue University, 1981-2013 (MS Environmental Engineering, 1976; PhD Air & IH 1981)

- Industrial Hygiene Consulting, 1983-present

How many years have you been volunteering for ACGIH?

I’ve been a member since 1981 but not too active until serving on the Industrial Ventilation Committee from 2018-2023, and then on the Board of Directors from 2023-present.

What drew you to volunteer with ACGIH?

I made a few suggested corrections to the GEV chapter of the Industrial Ventilation: A Manual of Recommended Practice for Design manual, and the next thing I knew, I was invited to become a member of ACGIH’s Industrial Ventilation Committee and was assigned to review and revise the chapter for the 31st edition.

What do you see as the most pressing issue in the field?

- Continuing and emerging hazards of nanomaterials

- IAQ with regard to infectious aerosols

- The inappropriate use of AI

What changes would you like to see in the field?

More public recognition of our profession and its importance.

How do you foresee the future of occupational health and hygiene?

I foresee a bright future, as there are always (unfortunately) going to be continuing and newly emerging workplace hazards.

Featured in

Mar. 21, 2024

edition of

Exposure

Weekly.

Robert F. Herrick, MS, ScD, CIH

What is your profession, and how many years have you been practicing?

I started in environmental health practice in 1973, at that point I was with the Army Environmental Hygiene Agency. We did studies ranging from air, water, hazardous waste, and workplaces. We were Environmental Science Officers and at one point the Army had us take a 2-week course taught mainly by people from the NIOSH Division of Training. That opened my eyes to aspects of EH that were connected directly to people’s health and well-being, so I kept that focus until I retired in 2018.

How many years have you been volunteering for ACGIH?

I started volunteering on a joint ACGIH-AIHA research task force in the late 1970s. I was involved in ACGIH committees on air sampling instruments and small business, then I had the chance to run for ACGIH Chair in 1990. That meant I served on the Board, then became Chair in 1992. Then I was Chair (again) in 2013.

What drew you to volunteer with ACGIH?

I volunteered for ACGIH, AIHA, and IOHA, and I found that ACGIH’s focus on the scientific aspects of our field was the most rewarding for me. The more I participated in ACGIH activities, the more I was amazed at the selfless dedication of the volunteers who gave their time and expertise to expand the scientific basis of our field. When the TLVs came under attack in the 1980s, it strengthened my resolve to support ACGIH. I knew the criticisms were baseless as I had seen the committee processes firsthand. But the costs of defending the organization almost bankrupted the ACGIH. I focused my second term as Chair toward revamping the financial basis supporting the organization.

What do you see as the most pressing issue in the field?

I had the good fortune to spend the second half (25 years) of my career in academia. The most pressing issue I see is that young, bright, energetic students choose EH concentrations other than workplace health and safety. I don’t find this to be a mystery – over the years I had so many students tell me that they liked our emphasis on human health and wellness, but they did not want their degree to be identified as industrial hygiene. Occupational hygiene was a marginally better term, but it still seemed like an antiquated brand. This isn’t a trivial matter as good students can choose concentrations called exposure science or something similar, which seem to connote a modern aspect of public health practice. IH is a term from the past.

What changes would you like to see in the field?

The field needs to rebrand itself or continue its slide into irrelevance. I’m not alone in this, several prominent colleagues including AIHA Past Presidents have made the compelling case that “industrial hygiene” is a misnomer that misrepresents what we actually do. Want proof? When people investigated the spread of COVID-19 and looked for solutions to control the pandemic, did anyone say “What we need is an industrial hygienist”? Even though we have the knowledge and skills needed, the term IH does not convey them.

Most notably, AIHA has failed to take the lead in rebranding the profession. As the profession’s primary membership association, AIHA needs to replace the term “industrial hygiene” with “occupational health” or a similar term that accurately depicts its members, and our capabilities.

How do you foresee the future of occupational health and hygiene?

The future of occupational health research is bright. Even though funding for research (especially from NIOSH) is tragically low, the knowledge base is impressively expanding. When it comes to occupational health practice, the extent to which research findings translate into practice is a function of the power balance between workers and employers. Disenfranchised workers have little leverage to motivate the implementation of health and safety innovations in the workplace.

Featured in

Mar. 7, 2024

edition of

Exposure

Weekly.

Pamela Susi, MSPH, CIH

What is your profession, and how many years have you been practicing?

I am an industrial hygienist and have been employed in that profession for thirty-three years.

How many years have you been volunteering for ACGIH?

I first volunteered for ACGIH serving on the construction committee in the 1990s and began serving as an ACGIH board member in 2020, so approximately six years.

What drew you to volunteer with ACGIH?

I initially began volunteering because construction workers were being exposed to extremely high levels of lead and silica and OSHA construction standards were lacking at that time. It wasn’t uncommon to hear about bridge workers getting lead poisoned. At the time, industrial hygienists were rare in construction.

What do you see as the most pressing issue in the field?

A major issue is that the agency charged with promulgating health standards is hamstrung by a rule-making process that allows business interests to turn down the spigot on standards development to a trickle. The result has been the publication of a relatively small number of OSHA health standards during the last forty years and permissible exposure limits (PELs) over 50 years old. This is why the ACGIH TLVs are so important. Both are essential evaluation criteria. But since an employer is only required to comply with the PELs, the protection offered employees is often woefully inadequate.

Given the history of OSHA and the role of organized labor in its creation and ongoing support, a grave, underlying concern is the decline of union representation of U.S. workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s January report, the number of workers represented by a union fell from over 20% in 1983 to 10% in 2023. OSHA rulemakings have no shortage of industry group representatives opposing health standards and standing ready to file law suits to at best weaken them. But those present to support them and/or strengthen them are fewer in number and unions are prominent among that group.

What changes would you like to see in the field?

I think we’ve done a good job of focusing on the technical aspects of our profession and have made major inroads in addressing industrial hazards. But some areas in which I think our profession could grow is by:

- Providing greater attention to: Women workers, especially with respect to PPE and ergonomic workstation design; Younger workers (including child labor); Public sector workers including firefighters, teachers/school workers and public safety workers who may experience physical hazards such as heat in the case of fire fighters, occupational stress, or violence – areas not historically within the realm of industrial hygiene.

- Involving workers more in hazard identification and in implementation of engineering controls which increases engagement and results in more effective outcomes.

I would also like to see us as a profession recognize that EPA and OSHA standards share some common goals. The Frank R. Lautenburg Chemical Safety Act for the 21st Century provides worker and family protections for a large number of chemicals and we need to get up to speed with how these provisions will be implemented in conjunction with OSHA standards.

How do you foresee the future of occupational health and hygiene?

- Younger workers may have higher expectations for safety and health conditions driving acceptance and demand for occupational health measures

- The focus on chemical hazards will need to expand more broadly to include greater emphasis on climate and resulting heat stress concerns, and other hazards generated from new technologies

- Greater expectation for industrial hygienists to address both occupational and environmental hazards and the contribution both may make to worker health in some cases

- There may be a need to redefine our “job description”, expand our skills, and/or identify allied professions as necessary to address the wider array of hazards associated with the 21st century workplace.

Featured in

Feb. 29, 2024

edition of

Exposure

Weekly.

William S. Beckett, MD, MPH

What is your profession, and how many years have you been practicing?

Occupational Medicine, Pulmonary Medicine (retired), practiced 36 years

What drew you to volunteer with ACGIH?

One of my professors in public health school, in my Industrial Hygiene course, was Morton Corn, who had been Chair of the Board of Directors of ACGIH. He described to us the history of the organization, and importance of TLVs in the prevention of occupational disease. I later also observed in my academic medical practice, seeing patients with serious occupational disease, that TLVs are a key part of prevention of occupational disease. When I was invited to join the TLV-CS committee, I was honored and enthusiastic to contribute. Participating in the TLV committee is the most important thing I am doing about occupational health. And I’m thrilled that our TLVs are observed in parts of Canada, Australia, and other parts of the world.

What do you see as the most pressing issue in the field?

Lack of highly trained industrial hygienists with a public health perspective in the US and also in many other countries.

What changes would you like to see in the field?

a.) Increased outreach to high-school and college-age students interested in Environmental Health to show them the career possibilities in Occupational Health.

b.) Increased lobbying Congress and state legislatures for more funding for OSHA and State OSHA staff, to improve enforcement of existing standards.

How do you foresee the future of occupational health and hygiene?

Our knowledge base is good, and with internet it is widely available worldwide. We lack sufficient recruitment of motivated young people to join our field as professionals.